Whatever Happened to the Future?

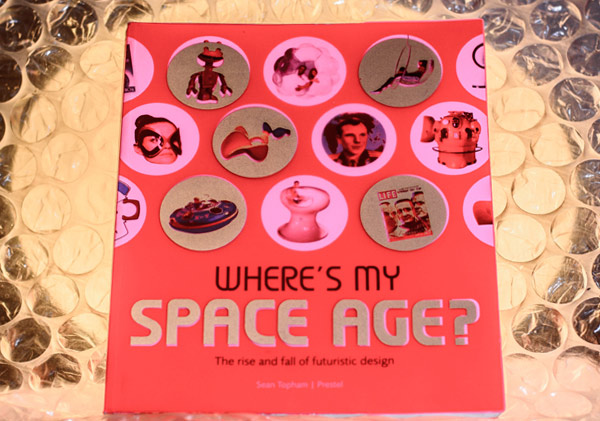

Recommended Reading: “Where’s My Space Age? – The Rise and Fall of Futuristic Design” by Sean Topham

Bubbles, amoebic blobs, and chrome. When you look at the space-themed objects from the 50s, 60s and 70s with their rounded shapes and saturated colours, you can’t help but smile. They look so playful and optimistic, like toys for grown ups.

Bubbles, amoebic blobs, and chrome. When you look at the space-themed objects from the 50s, 60s and 70s with their rounded shapes and saturated colours, you can’t help but smile. They look so playful and optimistic, like toys for grown ups.

Interior design photos from the period show models in sculpted environments, many of which are more pods than rooms. Minimalists will note that these idealised interiors didn’t have a lot of stuff cluttering up the view. If you wanted to, you could turn somersaults in a lot of these spaces.

What really grabs you is how imaginative everything was. Design was about exploration and play. People were looking forward to change. New materials (especially plastics) and new construction methods meant that new products were shaping themselves to us and not the other way around.

Architects were playing with modular rooms, buildings and cities, and looking for ways to make everything effortless. Technology was progressing faster than ever before, and changing us with it. Limitations seemed to be disappearing.

Then everything came to a screeching halt. In 1973 the oil crisis hit, bringing rampant inflation and economic austerity, and the party was over. People gave up on their dreams of having machines do everything for us, and started working longer hours than ever.

The future, it seems, was not all it was cracked up to be.

The World Shapes Design…Design Shapes The World

In “Where’s My Space Age”, Sean Topham chronicles the story of space themed design, from its postwar beginnings to its periodic resurfacing today. He provides excellent historical context for the incredible public appetite for anything referencing rocketry, astronauts and outer space – and how the design world both led and responded to this need.

The Future Is Now

Interestingly, it was not all about escapism, even if it started out that way.

In the 1940s, incredible and terrible advances had been made in aviation, rocketry and nuclear power. The atomic explosions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki showed just what a final trump card technological power could be.

After the end of the second World War, a weary public was more than ready to settle down to a quiet family life in the growing suburbs. Their radios, televisions and their childrens’ comic books brought them adventure stories, some of which were set in space and the future. People wanted to look ahead, not behind.

By the mid-50s, however, the cold war was in full swing, and space fever hit. The race was on, and former German rocketry and aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun was a celebrity. When the Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite circled the globe in October 1957, the possibilities of life beyond the Earth captivated the Western imagination. After the crew of the Apollo 11 mission landed on the moon on July 20, 1969, it must have seemed like humans could solve any problem and accomplish any goal.

Futuristic Dreams Meets Industrial Production

Designers are no different from the rest of us, and were excited by what was going on in science. Suddenly everyone had new kinds of products like clothing that fastened with velcro and teflon non-stick pans. Themes in the 50s referenced not only advances in rocketry and nuclear science but microbiology as well.

From the toys we played with to the tools we used and the clothes we wore, space fantasy themes were emerging from our dreams into reality.

In Our Homes

When new materials and new industrial production methods met our ideas of the future, a design revolution was born. Formable materials like aluminum became more widely available once the war was over. Advances in chemistry led to new plastics.

Both lent themselves to being shaped into the swooshes of the fifties and blobs of the sixties. While rocket fins turned the cars we drove into ersatz jets, atomic and UFO shapes started making their way into light fixtures, clocks and coffee tables.

In the late 1940s, Charles and Ray Eames solved the cracking problems that came with bending plywood and released the Eames Lounge Chair Wood, which was produced well into the 1960s. Eero Saarinen’s plastic Tulip Chair was a runaway hit in 1956, and Verner Panton’s Panton chair was the first chair to be created from a single piece of plastic. Designs like this paved the way for delights like Eero Aarnio’s Bubble Chair (1968), Pastil chair (1967) and Tomato chair (1971) which seemed to defy gravity.

We could all have a futuristic wonderlands in our own homes.

Left: the Panton chair by Verner Panton. Right: Tulip Chairs by Eero Saarinen. For image credits please see below.

Spaces – Public and Private

These shapes didn’t just appear on a small scale; the new methods and shapes were manifesting in architecture as well. Beginning in southern California in the late 1940’s, a spaceport-themed style known as Googie architecture took its name from 3 coffee shops designed by John Lautner. The elements of Googie were embraced by architects like Eero Saarinen with his TWA Flight Centre at the John F. Kennedy airport in New York (1962). Seattle’s Space needle opened in 1961, as did the Theme Building at the Los Angeles Airport.

Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, by Pereira, Luckman, Langenheim, Williams and Becket. For image credit please see below.

Private houses as well as public spaces were being rethought and reshaped. John Lautner’s Chemosphere emerged on a Los Angeles hillside in 1960. Its UFO shape belies a clever design solution to the steep slope it was built on. Matti Suuronen’s Futuro ski cabin landed in Finland in 1968. Perhaps the pinnacle of this design was achieved by Annti Lovag with the Bubble Palace. Completed in 1978, it was bought by futuristic fashion design icon Pierre Cardin in 1989. The space age was influencing where and how we live.

Home design was taking inspiration from modern production methods as well. Buildings could now be pre-shaped and easily assembled on-site. Often they could be transported and/or disassembled for easy transplantation on other sites. Jean Maneval’s Six Shell Bubble, produced in 1968, was the first entirely prefabricated house.

Even though we now live in the age of space tourism, furniture and architecture from the the 50s and 60s still looks avant garde to us. It’s like we had a reaction to the future once we were on the threshold, and have stepped back a few paces.

What Space Age Design Gave Us

But we haven’t left the future behind us entirely. Today there are a lot of ideas from the space age design era that we still love. On blogs and in news feeds, many of the ideas that still sound modern had their origin in the 50s and 60s. Perhaps we need more time to get used to the future.

Here are some of the “new” ideas I keep seeing that are repurposed from the 50s and 60s:

One-Piece Furniture

Traditional furniture takes incredible skill to build, and involves multiple pieces expertly carved and joined together in boxy shapes. Space age design brought more rounded shapes to our homes, and at least the illusion of single-piece design. With injection-molded plastic, you could get chairs shaped like ribbons, bubbles, or curvy blobs of protoplasm. Replicas of many of the most successful designs are still available today.

Inflatable Furniture

Lamps, beds, chairs and even rooms could all be constructed of inflatable plastic. Michael Webb and David Green’s 1966 “Cushicle” was an inflatable bed inside an inflatable bubble. This concept resurfaced in 2001 with the Chill Out Room, which (unlike the Cushicle) is opaque and can create private spaces where none existed before.

Modular and Prefabricated Construction

From bookcases to desks to homes, the idea of having units that combined in different shapes gives excellent flexibility. Modular homes stem from the early decades of the 20th century, but modular construction didn’t really take off until the post-WWII construction boom. When combined with the ability to prefabricate major pieces, you create the ability to erect simple, configurable but cost-effective housing. Some recent examples include these solar-powered homes for refugees, and there are many eco-friendly versions.

The idea that furniture could be made to be assembled into different configurations was born with metal office furniture by USM from designs by Fritz Haller in the early 1960s. You can still see these ideas in new ways from furniture companies today, including sectional seating and bookcases that can grow as your library does.

Transformer Homes

Many new homes are becoming smaller, and not just in Europe and Asia. Because of this we’re now seeing some wonderful “transformer” rooms like this one in Hong Kong and this one in Madrid. Rooms that transform from living room to kitchen to bedroom make optimal use of small spaces and adapt to our daily activities.

The future has already happened, it seems.

Read It

“Where’s My Space Age” is a great introduction to the design and architecture of what’s called the space age, the atomic age, retro and Googie. Brilliantly written and incredibly well researched, it provides far more detail than I do in this article. Its fun plastic cover promises plenty of visual appeal, and the book delivers with dozens of colour images throughout.

While it may be tempting to some to dismiss the architecture and design of this era as juvenile, Topham never succumbs, in spite of the fun title. Instead he explores the historical context of the rise, fall and periodic resurrection of the elements of space age design language. He connects it to people’s lives in a way that shows us why and how these design elements became so popular.

In our current era of economic austerity and ecological crisis, many people’s tastes are influenced by a romantic view of the past. Dozens of vintage styles have become popular again, but it’s odd to think that the word “antique” now includes furniture that still looks like it’s from the future. “Where’s My Space Age” will have you thinking about how economic moods effect designs, both in the past and as trends come and go in the future.

You’ll find yourself wondering what happened to the optimism that characterized the age, where it went, and why…

by Jennifer Priest

Image Credits

- Bubble wrap, book on bubble wrap: Justin Dane and Jennifer Priest

- Sputnik: NASA image

- Eames Lounge Wood Chair:

- Panton Chair: “Panton Stuhl” by Holger.Ellgaard – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

- Tulip Chairs: “Tulip med” by Source. Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia.

- Theme Building: “LAX LA” by monkeytime | brachiator – I’m stuck with a valuable friend. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

- Chemosphere:”Chemosphere 2012” by CDernbach – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

- TWA Building: “Jfkairport” by pheezy – Flickr. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

- Bubble Chair:Hans B. from nl [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], from Wikimedia Commons

No comments yet.

Add your comment